The very limited six-day run of Burn, Alan Cumming’s solo performance piece at The Joyce Theater, ends this weekend but there is so much joy in it that I can't resist celebrating it.

In 2008, Cumming opened that year’s Lincoln Center summer festival in an exuberant production of the seldom-performed The Bacchae that had him making his entrance by descending, upside-down, from the ceiling. Five years later he turned in an intense performance in a one-man version of Macbeth in which he played all the parts. He’s also written three memoirs and a children’s book, is a co-producer of A Strange Loop and the host of “Club Cumming,” a showcase for queer comedians that is currently streaming on Showtime (click here to check that out).

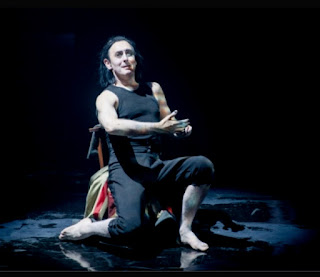

Now Burn is at the Joyce, the Chelsea venue for dance, because Cumming teamed up with the choreographer Steven Hoggett to create a movement-and-word tribute to the 18th century poet Robert Burns, revered as the national bard of their native Scotland.

After working on it for nearly seven years, the duo took the piece to the Edinburgh International Festival in August (click here to read about their journey). When word came that they were also bringing it here to New York, my always-up-for-anything theatergoing buddy Bill and I bought tickets to see it.

To be honest, the show is far from perfect. For starters, Cumming is not a trained dancer and, at 57, he often gets winded as he executes the movements that Hoggett and his co-choreographer Vicki Manderson have created for him to perform. The words he speaks are drawn from some of Burns’ poems but more so from the letters that Burns wrote and that reveal more about the man inside the icon. But, alas, some of those words were occasionally drowned out by Anna Meredith’s score, a crazy-quilt fusion of Scottish folk tunes and techno beats.

However in the end, none of that really mattered. Burns, the author of the New Year’s Eve classic “Auld Lang Syne,” is a compelling subject. The son of a poor tenant farmer, he was largely home schooled and spent most of his early years laboring on the farm although he never developed a knack for it and would struggle with making a living until he died at the age of 37.

Burns began writing mainly as a way to woo girls and he remained lusty throughout his life, siring 12 children, three out of wedlock and the last born on the day of his funeral. But his poems, an innovative mix of Scottish and English wordplay, eventually branched out to deal with such subjects as class inequality, the role of the church in society, the poet's own intermittent bouts of depression and his always abiding love for his homeland.

Cumming and Hoggett are proud Scotsmen too and both have worked often with the National Theater of Scotland, where they incubated this piece. As always, Hoggett, who has devised distinctive movement for such shows as Once, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, found surprisingly playful and inventive ways to tell Burns' story.

There were bits of stage magic—a quill pen that writes by itself—and other memorable images: the women in Burns’ life were represented by shoes that dangled from the ceiling on ribbons. Terrific videos by Andrzej Goulding and effective lighting by Tim Lutkin recreated the Scottish landscape and the peaks and valleys inside Burns’ mind.

And, of course, Cumming was as passionate and committed as ever. He never left the stage during the 60-minute performance and his obvious delight in what he was doing kept the audience right in the palm of his hand.

As Bill and I stood outside the theater after the show, he said how glad he was to have seen it. Me too.