Theater worked hard this year to come back from the pandemic. As part of those efforts, Broadway dropped its requirement that theatergoers show proof of being vaccinated and made mask wearing optional. Smaller off-Broadway theaters dropped the vaccination requirement too, even though many of them kept their masking mandates.

And there were so many new shows this fall that sometimes two or even three of them opened on the same night as producers rushed to serve up the theatrical equivalent of comfort food: familiar titles (there are currently four Pulitzer Prize-winning plays—Between Riverside and Crazy, Death of a Salesman, The Piano Lesson, Topdog/Underdog—running on Broadway) starry casts (Hugh Jackman, Sarah Jessica Parker, Vanessa Williams, Samuel L. Jackson, Daniel Craig, Daniel Radcliffe) and lots of Sondheim.

Some of those efforts were successful (several of those productions were terrific). But some weren’t (numerous performances, including the opening night of The Collaboration, the final Broadway production to open in 2022, had to be cancelled when cast members tested positive for the virus).

Even in the before times, it could be hard for me to single out what was the best in a theatrical year and it’s even tougher to do that in these still fragile times. So I’m going to leave the anointing of this year’s best to my critical brethren and sistren (click here to read my pal Jonathan Mandell's annual compendium of their choices). Instead, to paraphrase the great Oscar Hammerstein, here are just a few of my favorite things:

Seeing A Case for the Existence of God: No play moved me more this year than Samuel D. Hunter’s quiet two-hander that opened at Signature Theatre all the way back in May. It started off as an uneasy reunion between two former high-school classmates (one black, gay and college-educated; the other white, straight and working class) but under David Cromer’s sensitive direction it evolved into a more encompassing meditation on both the feelings of alienation that have so divided this country over the past few years and the things we all share in common, managing in the end to offer a ray of hope for better times to come.

Reveling in Michael Potts' performance in The Piano Lesson. There were plenty of performances I adored this year: Marylouise Burke in Epiphany, K. Todd Freeman in Downstate, Corey Hawkins in Topdog/Underdog, Linda Lavin in You Will Get Sick. But it was Potts who stood out most for me. In the midst of the dazzling constellation of stars—Danielle Brooks, John David Washington and Samuel L. Jackson—that director LaTanya Richardson Jackson assembled for this revival of August Wilson’s drama about the legacy of slavery, Potts stole every scene he was in with a performance that was so natural and so true that it didn't seem as though he was acting at all.

Discovering Lloyd Suh and Sanaz Toossi: One of the things I most love about going to the theater is finding new voices who allow me to see the world from a fresh perspective. Suh, a winner of this year’s Steinberg Award for mid-career playwrights; and Toossi, who only completed her M.F.A from NYU four years ago, each did that for me twice this year. His plays The Chinese Lady at the Public and The Far Country at the Atlantic looked at parts of the American experience that too often get left out of the history books. While her plays English, also at the Atlantic Theater; and Wish You Were Here at Playwrights Horizons upended conventional stereotypes about Muslims, particularly Muslim women, living in contemporary Iran. All four productions opened my eyes and made me eager to see what these playwrights do next.

Marveling at John Lee Beatty’s set for Chester Bailey at the Irish Rep. Sets don’t usually get attention unless they’re big and glitzy in some way. Beatty’s hauntingly beautiful creation was the opposite of that. It was just a unit set that didn't change much at all but with the help of Brian Levitt's exquisite lighting, it elegantly evoked New York’s old Penn Station, a WWII munitions factory and an isolated hospital ward as though it had been designed specifically for each location in Joseph Dougherty’s drama about the power of imagination to insulate us from even life's cruelest tragedies. The Irish Rep has always punched above its weight but this year it was one of the beneficiaries named in Stephen Sondheim’s will and it is clearly putting that money to good use.

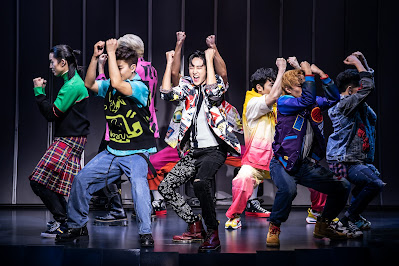

The casting of black leading ladies in musicals. Twenty-one musicals are running on Broadway during this holiday season and 15 of them have women of color starring in leading roles. It’s no surprise that shows like Aladdin, Hadestown, Hamilton, The Book of Mormon, The Lion King and A Strange Loop (its L. Morgan Lee is the first trans woman to get a Tony nomination) have non-white actresses in principal roles but those parts were written that way.

What got my attention is that this year Emilie Kouatchou became the first black actress to play Christine in Phantom of the Opera and Brittney Johnson became the first black actress to step into Glenda’s shoes full-time in Wicked.

And they were joined by Denée Benton as Cinderella in Into the Woods, Lorna Courtney as Juliet in & Juliet, Lana Gordon as Velma Kelly in Chicago, Adrianna Hicks as Sugar in Some Like It Hot, Kristolyn Lloyd as John Adams in the gender-flipped revival of 1776 and Solea Pfeiffer as the head groupie Penny Lane in Almost Famous. Plus there’s the rainbow coalition that have made up the cast of British queens in Six since its very beginning.

Such diverse casting is unprecedented for the Great White Way. And I can hardly imagine what it would have meant for a young me to have seen leading ladies who looked like me standing center stage and being so adored and so admired when I was coming up. Or what it would have meant for the non-black people sitting in the audience beside me.

And finally, if you’ll permit me, I’m going to add one more thing to this list:

Working on my BroadwayRadio podcast "All the Drama." For the past year and a half, I’ve been researching and talking to people about the select group of plays and musicals that have won the Pulitzer Prize. Putting the episodes together has been both really informative and great fun for me. And I hope that it will be enlightening and enjoyable for you too. You can check it out by clicking here.